Earlier this month, I spent a day working in the throwback world of DOS. More specifically, it was FreeDOS version 1.1, the open source version of the long-defunct Microsoft MS-DOS operating system. It's a platform that in the minds of many should've died a long time ago. But after 20 years, a few dozen core developers and a broader, much larger contributor community continue furthering the FreeDOS project by gradually adding utilities, accessories, compilers, and open-source applications.

All this labor of love begs one question: why? What is it about a single-tasking command-line driven operating system—one that is barely up to the most basic of network-driven tasks—that has kept people’s talents engaged for two decades? Haven't most developers abandoned it for Windows (or, tragically, for IBM OS/2)? Who still uses DOS, and for what?

To find out, Ars reached out to two members of the FreeDOS core development team to learn more about who was behind this seemingly quixotic quest. These devs choose to keep an open-source DOS alive rather than working on something similar but more modern—like Linux. So, needless to say, the answers we got weren’t necessarily expected.

Doing very little, very well

Jim Hall kicked off the FreeDOS project 20 years ago while he was an undergraduate studying Physics. Hall is now the IT Director at the University of Minnesota-Morris, and he's still working to keep the DOS prompt blinking. Hall just returned to the project after completing a master's degree program, and he says that group has between 30 and 50 active developers involved. (That's down from the hundreds who were active while pushing FreeDOS to its 1.0 release in 2006.)

While it's a small group, this is no rag-tag assemblage of DOS holdouts. Many of them do develop for Linux and other operating systems, work for commercial software vendors, or hold other technical jobs. They largely contribute to FreeDOS for the intellectual challenge. Pasquale "Pat" Villani, the man who contributed the kernel to FreeDOS, was for many years a lead software engineer at Digital Equipment Corp., Compaq, and then HP, working on various Unix operating systems.

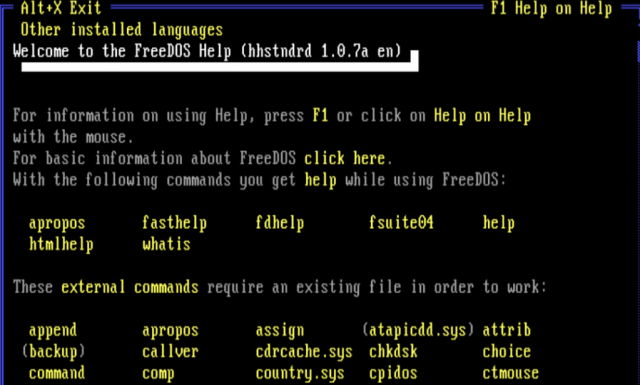

FreeDOS has a very loyal core constituency. Eric Auer, a long-time core contributor to FreeDOS, explained in an e-mail why he thinks DOS is still relevant. “It is small enough to get an idea of the inner workings,” he said. Auer said FreeDOS now has support for developers who want to do full-blown 32-bit applications thanks to the DJGPP toolkit, a port of the GNU Compiler Collection to FreeDOS. This allows developers to build monolithic applications that use all of the computing power of the machine they run on without the overhead of more complex operating systems. Also, Auer said, “It runs games that I knew 20 years ago.”

Because FreeDOS is, as some have called it, “barely an operating system,” it allows developers to get very, very close to the hardware. Most modern operating systems have been built specifically to avoid this for security and stability reasons. But FreeDOS has become much more friendly to virtualization and hardware emulation—it's even the heart of the DOSEMU emulator

The direction the project has taken hasn’t exactly followed the road map Hall envisioned after version 1.0. He once had ambitious plans for a next-generation of DOS, originally envisioning a modern FreeDOS along the lines of an alternative history of computing. “For a while, I was thinking, ‘If MS DOS survived, where would DOS have gone in the last 10 to 15 years?’" Hall said. "I was advocating some sort of multitasking—we could have task switching like what was supported in the 286, where you can put one process to sleep while you do another process. I wanted to have TCP/IP added to kernel.”

A group of developers started a FreeDOS fork project, FreeDOS32, after version 1.0 was completed. It was an attempt to create a full 32-bit version of DOS. But that project has flatlined; there hasn’t been any activity for at least two years. Hall came to the conclusion that DOS needed to be true to itself anyway. “As time went on, I realized, I have to face reality," he said. "People aren't going to go back to DOS to make it their platform of choice. So what DOS is, the core definition can't change."

As a result, the scope of development on DOS has moved away from tweaking the core of FreeDOS. “The kernel doesn't change much— it doesn't have to once you have feature parity,” Hall said. “The focus is more on drivers that give you more memory and other features… compilers and things more in the command line space are where people are doing the most development today. And that feels like a good place to be.”

Some modernizations are slipping in, Auer noted, “such as several types of USB devices, accelerated SATA/IDE UDMA drivers for disks, and optical media.” And some projects are bringing Windows-like applications to DOS, using code ports based on FLTK, a cross-platform light graphical interface library. “Those who really want to have a no-nonsense environment might use those for everyday work,” Auer said. “Others may use it just to experience the "coolness factor" of modern features being available in DOS.”

Three-hit wonder

Hall did an analysis of DOS users two years ago, finding that DOS was being called upon almost entirely to run three things: legacy bus software, classic DOS games, and embedded systems. “The fact that you get down to those three core users meant the ‘FreeDOS 2.0’ vision was getting ahead of us,” Hall said. “We'd lose our core audience.”

Today that core audience is larger than most people would imagine. There are a number of companies that continue to develop custom systems that run on DOS, because it lets them run close to the hardware. National Health Systems, for example, still sells a pharmacy system that runs on DOS.

FreeDOS isn’t the only player in this market. There are also a number of commercial embedded DOS vendors selling their own MS-DOS compatible operating systems for devices, such as DataLight’s ROM-DOS. Microsoft even still offers a version of MS-DOS for embedded systems to device manufacturers. “We have a couple people on our developer list contributing to FreeDOS because they're doing embedded systems,” Hall said.

Because of how close to the hardware FreeDOS is, it’s been used as a teaching tool for serial device programming, driver development, and as a developer platform for other embedded DOS environments. “People already have DOS programs, sometimes self-made ones, for controlling specialized devices,” Auer said. “DOS is a real classic, and you can run standard compilers and editors on it.”

In some ways, FreeDOS could be complementary to open-source “maker” tools like the Arduino microcontroller, but Auer sees Arduino and Raspberry Pi as being something else entirely. “Using Arduino means using a much smaller device, typically saving cost and electricity and offering more direct contact to your machinery. The disadvantage is not having any general purpose OS at all: if your Arduino software misbehaves, you have to use your ‘real’ computer to reprogram the Arduino instead of working directly on the Arduino.”

These sorts of questions become practical ones on the FreeDOS e-mail lists, according to Hall. “There was a guy I had an e-mail conversation with recently, debating about using Arduino or FreeDOS to deal with throwing the heating/cooling switch for heat pump—monitoring the temperature, and below a certain temperature throwing the switch.” Hall didn’t recall how that debate resolved itself.

Punch list

Of all its potential drawbacks, there is one major hole in FreeDOS today—its networking and Internet support. And sadly, “network and the Web are the two most important things to support today,” Hall admitted.

The operating system’s repositories include some basic networking capability, but there’s no real persistent network support. Individual applications can call on one of the open or free libraries available with FreeDOS to create a network connection, but each application has to configure its own communication. “DOS was designed long before TCP and networks, and it doesn't do networking in the kernel,” Hall said. “Apps now load their own support, and there’s not really any way we’re going to get away from that.”

That’s because the terminate stay resident (TSR) drivers that do exist for file sharing and persistent network access under DOS are almost entirely commercial software. These have long since lost support, so developing to take advantage of them is problematic. (ROM-DOS, for example, has its own “sockets” driver stack and includes tools for embedded applications to be controlled by telnet or even by e-mail—but the drivers are proprietary.)

Hall also admits that FreeDOS “needs better Web browsers.” The existing browsers we tested have been idle projects for some time. “They haven’t kept up with CSS standards and JavaScript support—you can understand that, but if you don’t have a browser that supports JavaScript in 2014, it’s hard to do much.”

There are plenty of reasons why doing Internet applications on DOS is hard—and in many ways, the reasons are antithetical to what makes DOS attractive to its core audiences. “DOS is neither a network-oriented nor a multi-tasking nor a multi-user operating system,” Auer said. “You can run things with very little overhead on easily available and replaceable hardware with very short boot time, [but] if you want to do high performance computing, using more than your first CPU core and first 3 to 4GB of RAM gets really ugly in DOS. People forget that if they try to 'simply' run browsers or office software on DOS, said software will have to bring most of the complexity that they wanted to get rid of with it to DOS, as DOS itself simply has no GUI, no multitasking, no Unicode TTF, no networking and so on.”

So don’t expect huge clouds of FreeDOS-based gaming servers any time soon. Don't expect Chrome for DOS. But in the long term, that may not matter, as FreeDOS’ parts find their way into places no DOS has gone before.

“We did have someone try to launch an effort a couple of months ago to see what would it take to bring FreeDOS to ARM,” Hall said. “You don't need a ton of power for DOS, but it’s probably going to be a lot of coding because DOS assumes there’s a BIOS. You could do some emulation and other things in the middle to fake it as far as the kernel is concerned—I’d really like to see that happen.” Hall also sees the potential for FreeDOS “inside another container—for example, what if you had a minimal Linux environment that boots up DOSEMU (the DOS emulator, which can run FreeDOS).” Hall said that could give people the equivalent of a multitasking DOS.

Auer said ultimately the applications of FreeDOS aren't what will keep devs interested. Instead, it's the same thing driving interest today that drove many contributors to computing in the first place—the tinkering aspect.

“I generally think having fun with DOS is an important factor,” he said. “In that sense, it is also a bit like a model train. You can learn to know a lot about it, and you can do a lot with it yourself, but you would not use it for your daily commute. Of course, DOS also still is important for those who worked with it because it lets them keep their old custom-made software. Sure, some ARM board might run the milling machine in your wood workshop as well, but the DOS software you wrote for it probably still works, and using a FreeDOS PC to run that makes it more pleasant than having to stress about new Windows compatibility of your old tools or new hardware compatibility.”

reader comments

90